‘ Bij het lezen van Kuczynski & Witt vallen parallelen op met hetgeen er momenteel, hier bij ons, gebeurt. Vind je niet?’

– ‘ Vervang bijvoorbeeld joden door boeren. De middenstanders kunnen gewoon zo blijven staan. Die worden evengoed gemarginaliseerd en uitgegumd.’

‘ Alarmbellen?’

– ‘ In ieder geval bij mij kleine alarm belletjes. De permanente staat van oorlog waarin de neocons “ons” lijken te willen houden. Tata Steel dat hier mag blijven produceren – met een groene marketing-smoes als schaamlap. Unheimische overeenkomsten.’

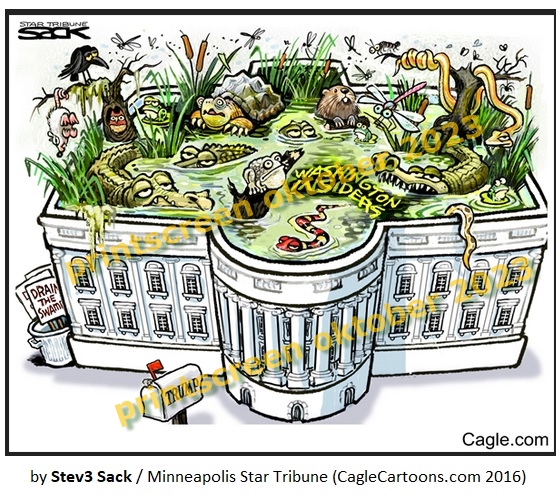

‘ Reken maar dat de Amerikaanse deep state heeft geleerd van de rampzalige proxy-oorlog tegen de Russen, in de Oekraïne. Ze zullen de wapen-productie opvoeren en het land als het kan in een oorlogseconomie houden. Dat betekent dat de Amerikaanse burger nog meer wordt afgeknepen en uitgehongerd en dat de infrastructuur verder wordt verwaarloosd. Intussen worden we ontregeld door tsunami’s van exoten en griezelig ondermijnd door woke-en-weet-ik-niet-wat- nog-meer.’

– ‘ Waar heb je deze teksten opgescharreld?’

‘ Van het oud papier. Toevallig. Ze zouden in de papiercontainer worden gekieperd. Dat incunabel van Kuczynski & Witt schijn je niet meer te kunnen krijgen bij de reguliere boekverkoper.’

– ‘ Het lijkt op een (gedeeltelijke) blauwdruk, een masterplan, aan de hand waarvan de globlablalisten hun Great Reset uitrollen.’

‘ Het idee van een wereldheerschappij willen stichten, is natuurlijk niet nieuw, alleen de wijze waarop wisselt. Tegenwoordig zijn “het Klimaat” en “het Virus” de voornaamste boemannen, maar Putin Xi komen daar als externe dreiging vlak achteraan.’

– ‘ Het artikel van Sheldon Wolin over autoriteit, gezag en macht, is mooi als complementaire tekst bij dat “signalement” van de ROB. ‘

‘ Ik heb de link naar ROB-rapport erbij gezet.’

………. …………….. …………….. ………………… …………………..

www.raadopenbaarbestuur.nl/documenten/publicaties/2022/11/10/gezag-herwinnen.-over-de-gezagswaardigheid-van-het-openbaar-bestuur.

Citaat van Sheldon Wolin (1994): The context for reading Weber’s abstract terms is political, and for the reading of his methodological essays it is political and theoretical. We can begin to construct the context for his terminology by noting the peculiarities of translation surrounding Herrschaft. It is often translated as ‘authority,’ but it is not an exact equivalent of die Autorität; and the meaning of Herrschaft is only obfuscated when translated as ‘imperative coordination’ by Henderson and Parsons.

Although Herrschaft may refer specifically to the estate of a noble, a reference which was taken up by Weber in his distinctions between patriarchal and patrimonial dominions, Herrschaft typically connotes ‘mastery’ and ‘domination.’ Thus Weber would write about the ‘domination (Herrschaft) of man over man.’ This means that while in some contexts it may be perfectly appropriate to translate Herrschaft as ‘authority’ or ‘imperative control’ and to emphasize the element of ‘legitimacy,’ it is also important to attend to the harsher overtones of Herrschaft as domination because these signify its connection to a more universal plane: ‘The decisive means for politics is violence … who lets himself in for politics, that is, for power and force as means, contracts with diabolical powers.’ Conflict and struggle were endemic in society as well as between societies. ‘ “Peace” is nothing more than a change in the form of conflict.’

Even when Weber addressed what seemed on its face a purely methodological question, he transformed it into a political engagement, stark, dramatic, and, above all, theological. Thus in the context of ‘a non-empirical approach oriented to the interpretation of meaning,’ he wrote: ‘It is really a question not only of alternatives between values but of an irreconcilable death-struggle like that between “God” and the “Devil.”

Even a casual reader of Weber must be struck by the prominence of ‘powerwords’ in his vocabulary; struggle, competition, violence, domination, Machstaat [sic], imperialism.

The words indicate the presence of a powerful political sensibility seeking a way to thematize its politicalness but finding itself blocked by a paradox of scientific inquiry. Science stipulates that political expression is prohibited in scientific work, but the stipulation is plainly of a normative status and hence its ‘validity’ (to use Weber’s word) cannot be warranted by scientific procedures and is, therefore, lacking in legitimacy. The same would hold true of all prescriptions for correct scientific procedure. As a consequence, instead of a politics of social scientific theory, there was the possibility of anarchy.

Sheldon S. Wolin (1994:292-293) Max Weber: Legitimation, Method, and the Politics of Theory.

In: Asher Horowitz: The Barbarism Of Reason: Max Weber And The Twilight Of Enlightenment. ISBN-13: 9780802005588; ISBN-10: 0802005586.

*

Jürgen Kuczynski and M. Witt (1942:19,20) (geredigeerd citaat):

The first six years of fascism in Germany, from 1933 to 1939, were also used to develop the technique of plain economic robbery. Various methods were experimentally tested on an increasing scale, with the Jews as chief material for research. It often began by what is called “the squeeze”: Jews were forced to pay for permission to continue in business. This method was followed by that of the “squeeze-out”: no raw materials and no government contracts were given to Jewish-owned businesses. A variation of this is the forced sale – forced, not because of economic difficulties, but because of hooligan terrorism and government pressure. More primitive methods, such as putting the owner into a concentration camp or even murdering him, were also resorted to. In fact, all the methods later applied in the conquered territories were first employed in Germany.

If we ask, “Who really benefited from this policy?” the answer is simple: the heavy industries, that is, the armaments industries; and the other big concerns, trusts and monopolies. At first sight this answer needs no additional illustration. Krupp and Voegler, Stinnes and Wolff, Poensgen and Schmitz, the representatives of coal and iron, steel and chemicals, are the men behind the throne, the real rulers of Germany. They are the ones for whom this new political system has netted hundreds and thousands of millions.

But, one may ask, did not the small firms, the numerous independent craftsmen and shopkeepers, the smail farmers and peasants, gain anything from the increase of production and business activity? They not only gained nothing; they lost heavily. They became the economic victims of this system. Thousands, nay, hundreds of thousands, of them saw their business fail; they were the economic equivalent of cannon fodder in the armed war.

There are two reasons for this, which, in effect, are but two aspects of the same process. In order to prepare as quickly and efficiently as possible for war, it is necessary to produce where production is most efficient and to utilize man-power where it can best be used. Now, small firms – and particularly the small-scale production methods of the independent small workshops-are not as efficient as the factories. Similarly, the distribution of goods is more economically organized if it proceeds through a relatively small number of big stores than through innumerable small retailers. Therefore, with their customary ruthless ness, the National-Socialists and monopolists instituted a large-scale massacre of small businesses. The former owners of these businesses and their employees were then forced into the armaments factories.

*